In the first two posts of this series, OAuth2 Access Token Usage Strategies for Multiple Resources (APIs): Part 1 and OAuth2 Access Token Usage Strategies for Multiple Resources (APIs): Part 2, we examined different approaches to reusing OAuth2 Access Tokens for different resources (APIs advertised on an API Gateway).

We looked at how OAuth2 Scopes and a concept of audience (or limitation of what service a token is valid for) impacts the reusability of these tokens. We looked at how these concepts could be incorporated into the existing OAuth2 and OIDC specs; there are several patterns and which one makes sense depends on the use case. We also looked at how each approach could be implemented, taking hints from common usage patterns and relevant specifications. Those specifications don’t prescribe exactly how to implement these use cases, but they do provide some hints.

In this final post, we look at some of the supporting concepts that impact how the options would work and which implementation approach you might use.

OAuth2 Access Token Usage Strategies for Multiple Resources (APIs): Part 3

Follow-Up To Token Request Mechanisms in Part 2

Recently, the IETF OAuth Working Group has introduced draft standards that formally define the resource parameter for Authorization Endpoint and Token Endpoint requests and an audience (aud) attribute in a JSON Web Token (JWT) acting as an OAuth2 Access Token. First, see the “OAuth 2.0 Current Best Practices” draft, Section 4.8. This further references another draft standard called “Resource Indicators for OAuth 2.0.”

The new draft standard’s approach is to specify multiple resources with multiple resource parameters, such as:

GET /as/authorization.oauth2?response_type=code

&client_id=a_blog_post_client_id

&state=jdodavcljkvbpoviojdkaacvxiuzcxoivulv

&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fapp1t%2Eiyasec%2Eio%2Fcallback

&scope=calendar%20contacts

&resource=https%3A%2F%2Fapp1.iyasec.io%2F

&resource=https%3A%2F%2Fapp2.iyasec.io%2F HTTP/1.1

Host: idp.iyasec.io

While JWTs are still not a mandated token format, if JWT is used as an Access Token, then the audience (requested resource) where the access token is valid can be specified as shown in the following:

{

"iss": "https://idp.iyasec.io",

"sub": "iavlkklmsfiilblzlkjvc",

"exp": 1403203400,

"scope": "read",

"aud": "https://app1.iyasec.io/"

}

The “OAuth 2.0 Current Best Practices” draft describes several mechanisms in Section 4.8 that will increase the overall security of Access Tokens, including:

- metadata mechanism that describes communication with known resource servers.

- Sender-Constrained Access Tokens via “OAuth 2.0 Token Binding”, “OAuth 2.0 Mutual TLS”, “OAuth 2.0 Signed HTTP Requests” or “JWT Pop Tokens.”

None of these is widely deployed, and we’ll save exploring them for a future post.

The same section, however, also describes Audience Restricted Access Tokens—which are a major theme and an assumption of this blog series.

Token Caching

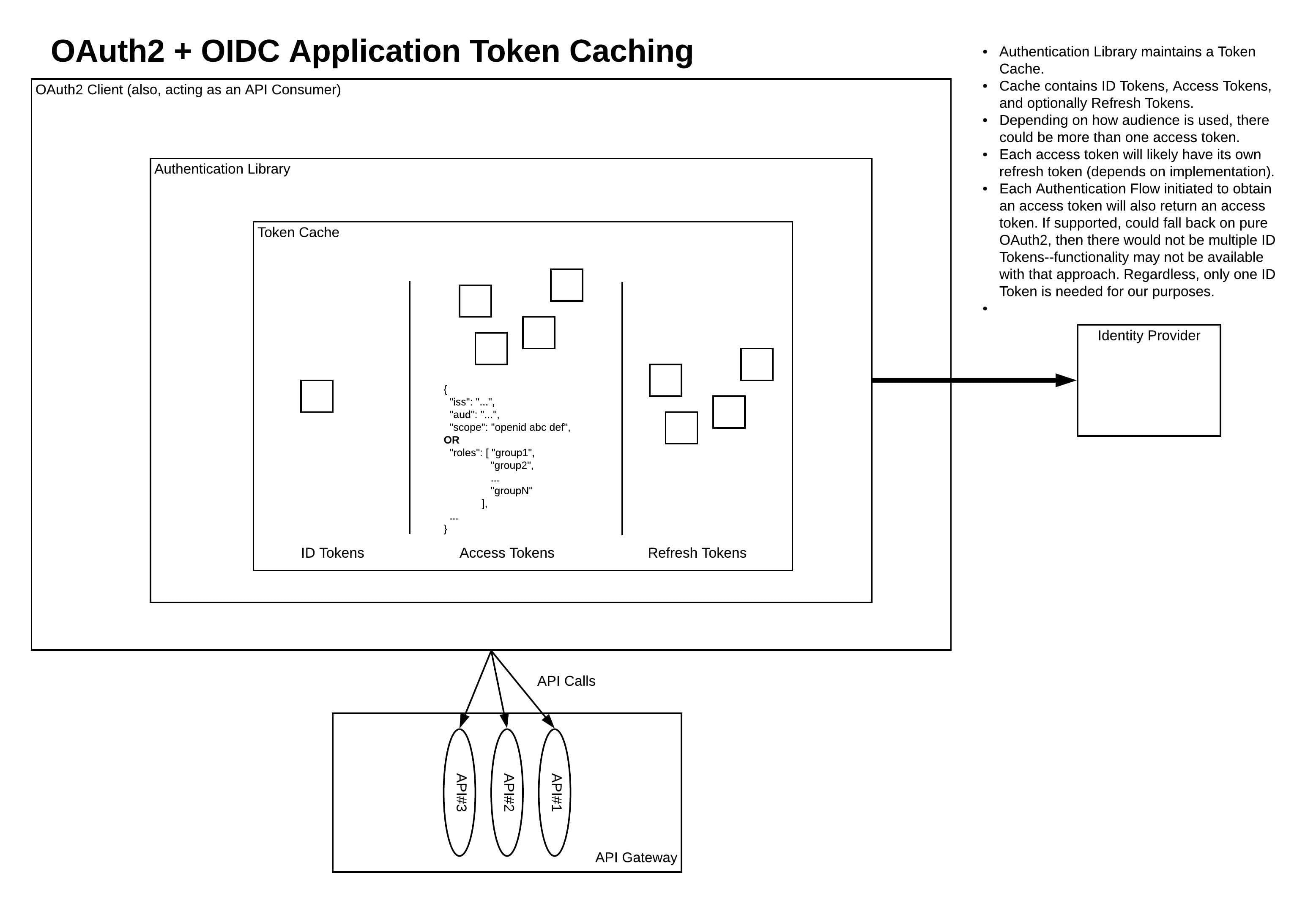

Token Caching on the API Consumer (which, for our purposes, would be the same as the OAuth2 Client Application) side of an API invocation (see diagram below) is very important to performance. Ideally, an (OAuth2) client-side authentication library would be used that implements this token caching rather than the developer implementing their own caching layer. Depending on the token usage strategy, the requirements for token caching will vary.

Note: The OAuth2 clients we’ve been considering in this series are native mobile apps and Single Page Applications (SPAs). The diagram shown below assumes a use case similar to one of those two types of applications. Other application architectures that are supported by the OAuth2 and OIDC specs will look different, but generally have similar concepts. Javascript applications running in the browser should adhere to the recommendations in the IETF draft “OAuth 2.0 for Browser-Based Apps.” Most relevant here are the comments in “Section 8: Refresh Tokens” and several parts of “Section 9: Security Considerations.” Likewise, for Native applications (mobile or desktop), read “OAuth 2.0 for Native Apps” (RFC8252).

Token Caching is depicted in the following diagram:

Audience Restriction Enforcement

The conversation we had about audience in Part 2 is very similar to the conversations I was having not so long ago about SAML with SOAP, WS-Security and WS-Trust. The concept of an audience or address where a token is supposed to be valid exists in these specs as well. Should the audience be used (per spec, yes)? How granular should the audience be (i.e., does it represent the service, the operation, something else)?

Back in the day, it was common to skip audience checks in SOAP Web Service authentication (with SAML) in some technology stacks. On some platforms, audience checks were virtually non-existent and, on others, one was forced to utilize the audience concept. So, the concept was not consistently used. Restricting which services (or endpoints) can be accessed with a security token by enforcing audience restrictions adds an additional layer of security by limiting where tokens can be used and where those tokens can be abused. It also adds a great deal of complexity to the use of security tokens like SAML or JSON Web Tokens (JWT). (Recall from our earlier discussions that we’ve assumed that the OAuth2 Access Tokens are all JWT.)

Resource Servers should enforce restrictions on what audience is allowed to be listed in OAuth2 Access Tokens. This limits the potential for unintended token reuse or the attack surface area if a token is compromised, by ensuring tokens can only be used to access the intended resources.

API Authorization Policy

Regardless of how the access token(s) is used across APIs and the semantics of the information it contains (or represents), each API must have an authorization policy that describes what types of users or applications can access the API. This authorization policy is highly application-specific (and to a slightly-lesser extent, organization-specific). The authorization policy could be business role-focused or resource-specific. The authorization policy could represent permissions that are assigned to an application by default, derived from a set of delegated permissions that the authenticated user gave them access to (the heart of what OAuth2 is all about), or depending on who/what owns the data, may simply be assigned by upon user role.

The first requires much more planning and discipline; in this model, every API endpoint and operation is mapped to a business role. This requires forethought and ground work that has translated the business organization into an identity model (roles). In an enterprise organization, this isn’t going to be done as part of a single project, but rather a distinct purpose-driven effort whose deliverable is the identity model. This is one of those abstract things that will always seem to be funded “next year” in many large organizations.

The easier approach, often taken by individual projects with no prior art to build upon, is to build an authorization policy based around the API and its operations (or, at least, a concept of read and write access).

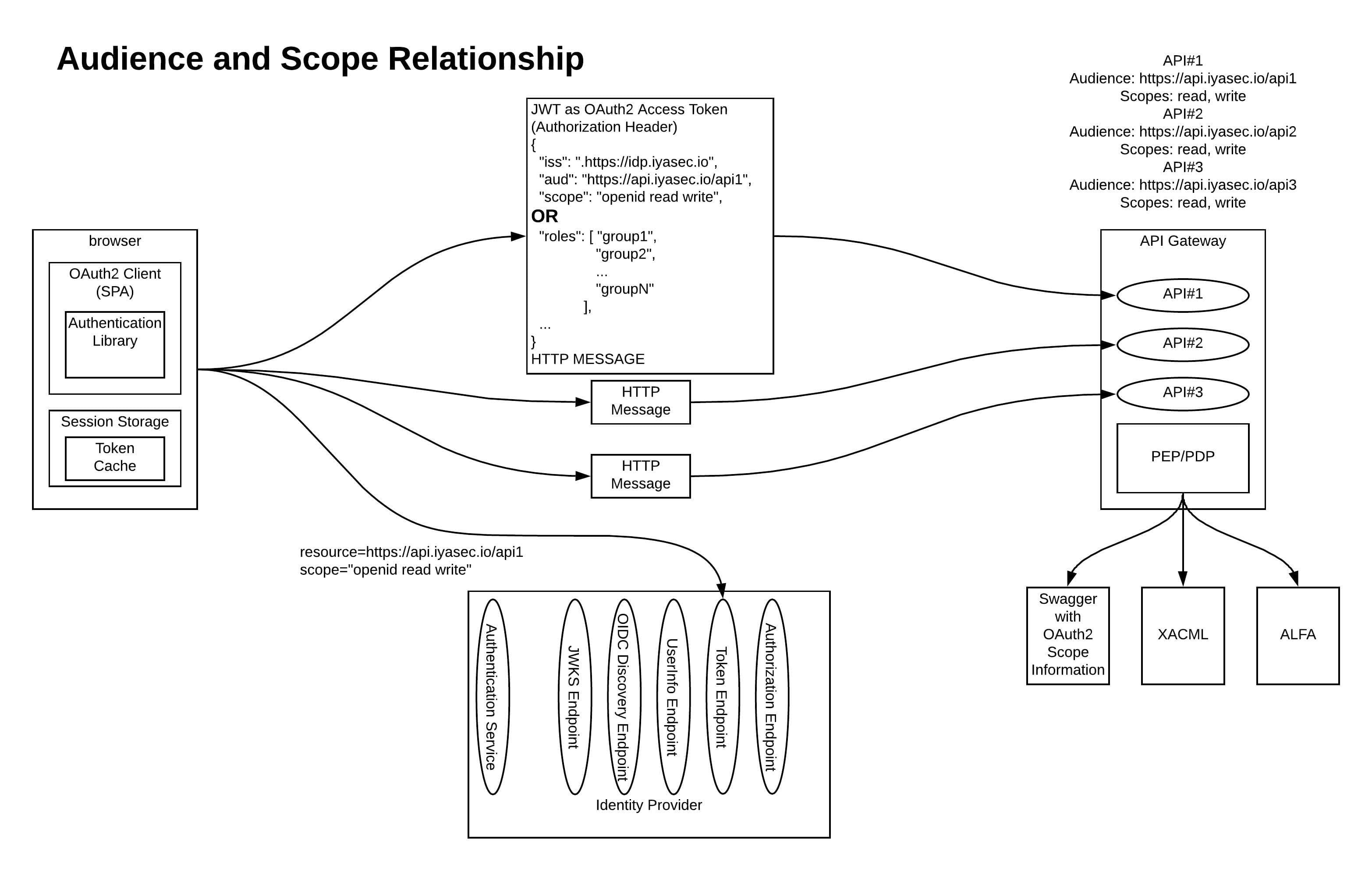

You can see an example of each approach of building an authorization policy in the following diagram:

Click here to view a larger version.

Regardless of how the authorization policy is defined, it should be there, and the API Gateway should be the first layer of enforcement of that authorization policy. Now, the API Gateway cannot know all those application API Authorization Policy-specific peccadillos that will bubble up into your APIs’ authorization policies. So, I advocate two layers of authorization enforcement in the application run-time: one at the API Gateway layer that is usually a form of Role-Based Access Control (RBAC, described above) called Coarse Grained Authorization (CGA), and one built into the application logic that has full access to the application context and all data needed to make authorization decisions (think the application database) called Fine Grained Authorization (FGA).

The terms CGA and FGA have been criticized because they are vague and tend to mean wildly different things across organizations. Here, I am using the following simple definition:

- CGA is the RBAC decision that is enforced at the API Gateway layer.

- FGA is anything more complicated than this that is moved back into application code where greater context is available.

In other implementations, the API Gateway is used to enforce permissions delegated to the application (either implicitly or explicitly) and the application code would enforce any user-specific authorization decisions. Regardless of how you classify these things, there are almost always going to be two layers of authorization decisions spanning the API Gateway and the API Provider.

Given all of that, if something like XACML or ALFA (Abbreviated Language For Authorization) is used at the API Gateway layer, a very rich authorization policy could be defined across a wide variety of situations. However, you also risk making the API Gateway more complex than it was originally intended. It is also unlikely that the API Gateway is ever going to have access to the application-specific datastores that would be needed to make the most complex authorization decisions. There will be more on XACML and ALFA in a future post.

Additional Thoughts

As you address which implementation approach(s) best suits your environment, here are some items for you to consider:

- At some point, the user will need to log out of the application. Besides the normal OIDC logout tasks, each additional access token (refresh token, etc.) that was obtained will need to be invalidated. In theory, this could be addressed by the OIDC Front-Channel Logout spec’s global logout functionality; however, it would involve a series of redirects that could prove to be quite fragile.

- If your application needs to support behavior described in the OIDC Session Management spec, additional complexity is introduced. I’m not going to attempt to address that in this post.

- Additionally, since the access tokens are JWTs, a resource server that is using a JWT validation library and the IdP’s OIDC Discovery Endpoint to validate access tokens (assuming the access token JWTs are digitally signed with the same certificate that the ID Tokens are) wouldn’t realize that those tokens are now invalidated — at least, not until the token naturally expires. If different signer certificates are used for Access Tokens and ID tokens, it is very likely a logical equivalent of the JWKS endpoint exists for access tokens — this is an IdP implementation detail. If the Resource Server (i.e., API Gateway) relies upon the IdP’s Token Introspection Endpoint to validate access tokens (not nearly as efficient), this problem doesn’t exist.

- For this discussion, we’re not taking token delegation into account (that’s where each actor that needs to make a downstream call on behalf of the original caller obtains a new token with the audience (and scopes) of the downstream actor). The addition of the downstream token wouldn’t invalidate anything described here, but it would add new concepts and complexities.

- Rather than a scope field, we could use a custom roles claim (probably an array of strings). Most of what has been described in this post would translate directly to the custom roles claim approach. What a user role represents versus what an OAuth2 Scope can or should represent is a topic for a future blog post.

- It would also be easy to eliminate the concept of audience from the JWT access token. Then, the trust of tokens extends to the entire trust realm (all actors that trust tokens issued by the IdP with that signer cert + issuer). This approach is sloppy and could have unintended consequences, and the use of JWT validation libraries hides additional complexity from application code, but it has been done before.

Choosing the Best Approach

The best approach to using access tokens with multiple resources depends on the scenario being addressed, what the IdP supports, and how the authorization policy is defined on the resources being accessed. In short:

- If your application is accessing one backend API, only one access token is needed. That token will have one audience and relevant scopes for the one API.

- If your application is accessing multiple APIs on the same API Gateway, then using one of the options described here (taking all caveats into consideration) would be used:

- If your platform can support it, the best approach is to obtain a unique access token for each backend resource. This is complex, but with the recommendations in this series, it can perform well and prevents unnecessary information leakage to downstream actors.

- The next best option would be to utilize multi-audience tokens.

- Avoid using a single global audience or no audience at all.

- Use the mechanisms described in “Resource Indicators for OAuth 2.0” in the long-term when the major IdP vendors support it.

I hope this series on OAuth 2 Access Token usage strategies, with its overview of fundamental usage questions and detailed look at scope and audience, has been useful to you. For information about leveraging identity and intelligent cybersecurity to prevent API misuse, please visit Ping’s API and Data Security page.

Start Today

Contact Sales

See how Ping can help you deliver secure employee, partner, and customer experiences in a rapidly evolving digital world.